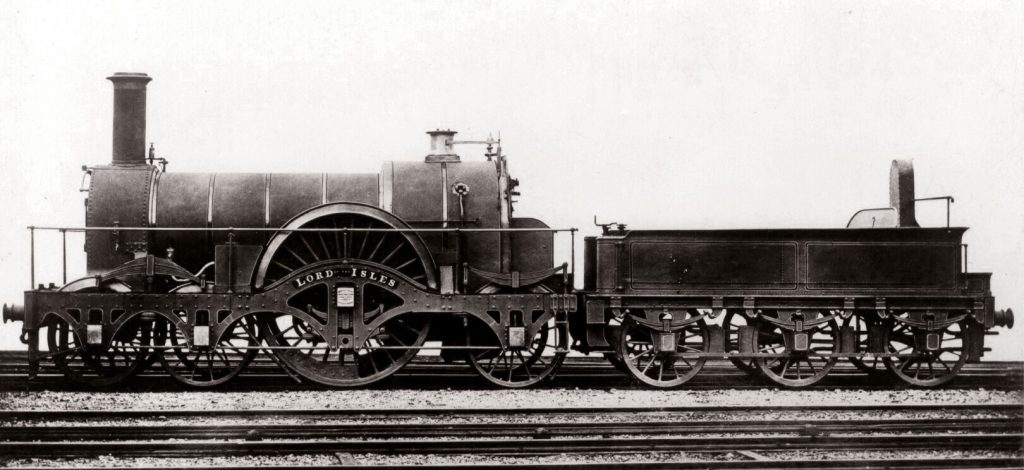

The day before the opening of the broad gauge line to Birmingham, a special train for Directors, Officers and friends left London at 9 a.m. for Birmingham. The train was heavier than had been expected, consisting of ten carriages, weighing together including passengers about 102 tons. Only an empty second class carriage was equipped with a brake and this was located next to the tender. The train was drawn by the powerful engine, “Lord of the Isles”, which had been much admired at the Great Exhibition in London.

The Officers on the train enquired at Oxford how long the local train had been gone. The station staff made a hasty calculation and replied thirty-three or thirty-four minutes. This was a mistake of ten minutes that tended to throw the parties in charge off their guard.

As the special train drew near the Aynho station the speed was slightly checked and the crew looked out for the first appearance of the station’s signals to know whether the line through the station was clear. Unfortunately, none of the crew were familiar with the district and this lack of knowledge of the local features of the line caused them to make a mistake.

The Aynho station is situated on a curve which sweeps round to the left on a radius of about two miles. The sweep prevents the station signal being seen until 800 yards from the station. A fixed signal 1000 yards from the station indicated the line was clear. The engine crew on the footplate, which included Daniel Gooch, did not know that the signal had ceased to be used and put on steam to accelerate their speed. While speeding onwards, the engine driver (Bob Roscoe, my great-grandfather) suddenly called out that the station signal was at “danger” and every effort was made to stop the train. It was too late, however, because the braking power attached to the train was very small as compared to the heavy load, and the train was running at high speed on a descending line.

The local train was late, as it had been for weeks, and had only been at Aynho station for five minutes as the high speed special train approached. The “Lord of the Isles” struck the goods wagon, which had been detached from the local train, breaking off the body from the wheels and throwing the whole body forwards onto the next goods wagon, whose rear wheels were thrown across the left hand rail. This obstruction threw the massive engine off the rails, which came to a stop rubbing along the platform side. Bob “stuck by his engine”. Fortunately, no-one on the special train was injured as the stability provided by the wider gauge meant all the carriages remained upright.

The passengers on the local train were not so fortunate. On seeing the special train approaching, the driver put on steam to get away, but only pulled the carriages which composed the passenger portion of the train. The coupling which connected the last carriage to the goods van had snapped under the sudden jerk and the goods van with the three wagons attached to it remained behind. The special train hit the stationary van and wagons with such force that they overtook and came into violent collision with the receding carriages.

The carriages were not damaged very much, but the passengers who rode in them were shaken and some injured. Six passengers who had intended to travel further ended their journey at Aynho as a consequence of their injuries. The local train took its carriages to Banbury and then returned to Aynho to take the special carriages to Leamington Spa where the company officers spent the night.

Clive Mortimer

2020

Notes:

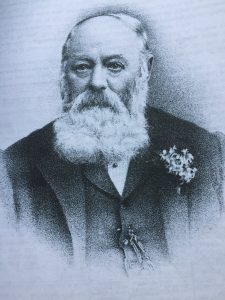

1, My great-grandfather, Robert (“Bob”) Roscoe, was born in Worsley, Lancashire, in 1818. He joined the Great Western Railway in 1844 as an engine driver after ten years on the Manchester and Leeds Railway. He drove the locomotive “Bright Star” from 1844 to 1847, then the Iron Duke “Sultan” on expresses from Paddington to Bristol and Paddington to Birmingham. From 1867 to his retirement in 1883 he drove “Lord of the Isles” and was available as the Royal Train driver when required. The Windsor to Paddington line was known as “the Roscoe Line”.

2. Bob Roscoe’s work and character has been well described by Adrian Vaughan in his book Grub, Water and Relief: Tales of the Great Western 1835-1892, John Murray, 1985 (p.90):

“Bob drove Sultan on the Paddington to Bristol and the Paddington to Birmingham expresses for twenty years, working twelve-hour shifts on a cabless locomotive at speeds of 60 mph through nights of bitter cold or drenching rain with the same unfaltering concentration as through a warm summer’s day. When his eyes were half frozen in the frosty slipstream and his brain craved sleep, ceaseless vigilance was essential if he was to keep check of where he was in the darkness so as to know what lay ahead and where to look to spot the next little signal lamp as early as possible. The signalling system was primitive, his brakes were quite useless for an emergency stop and his life and those of his passengers depended on his seeing his signals well before he got to them. In this his life was no more difficult than any other ‘top link’ driver, but he was notable, if not unique among express train drivers, for the relaxed and good-humoured manner he adopted towards the rest of humanity in spite of every difficulty”.

3. After the Aynho accident the following safety recommendations were made

- Discontinue the practice of mixing up goods wagons with passenger carriages on the same train to avoid irregular delays

- The Company should make an effort to ensure a greater degree of punctuality

- No train should run without a guard and a guard’s brake upon the last carriage.