Cyril Beeson (1889-1975) chose to retire to Adderbury in 1946 and lived in Westway Cottage, West Adderbury, until shortly before his death in 1975. During his time in Adderbury he gained a reputation as a local historian and particularly as a historian of clocks, especially North Oxfordshire clocks, including Quaker clocks.

EARLY LIFE AND SCHOOLDAYS

Cyril Beeson was born in Oxford on 10 February 1889 to Walter Thomas Beeson and Rose Eliza Beeson, née Clacey. Walter Beeson was Surveyor to St John’s College, Oxford. and a lifelong college employee. Beeson attended Oxford High School for Boys. His best friend there was T.E. Lawrence (known to Beeson as “Ned”, but better remembered today as “Lawrence of Arabia”). Lawrence called him by his nickname of “Scroggs”. In this photograph of the sixth form Ned (who took the photograph with home-made remote control) is on the right, with Cyril Beeson standing next to him.

The pair had a passion for medieval history and were well-known for cycling here, there and everywhere together in Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire, looking at churches and rubbing brasses. Closer to home, the two schoolboys took advantage of a great deal of building and rebuilding work in Oxford and toured building sites on a daily basis to collect any medieval glass or pottery that the workmen had found, paying them a few pence each time. They passed the most important of their finds on to the Ashmolean Museum. The Ashmolean’s Annual Report for 1906 said that the pair “by incessant watchfulness secured everything of antiquarian value which has been found”.

UNIVERSITY

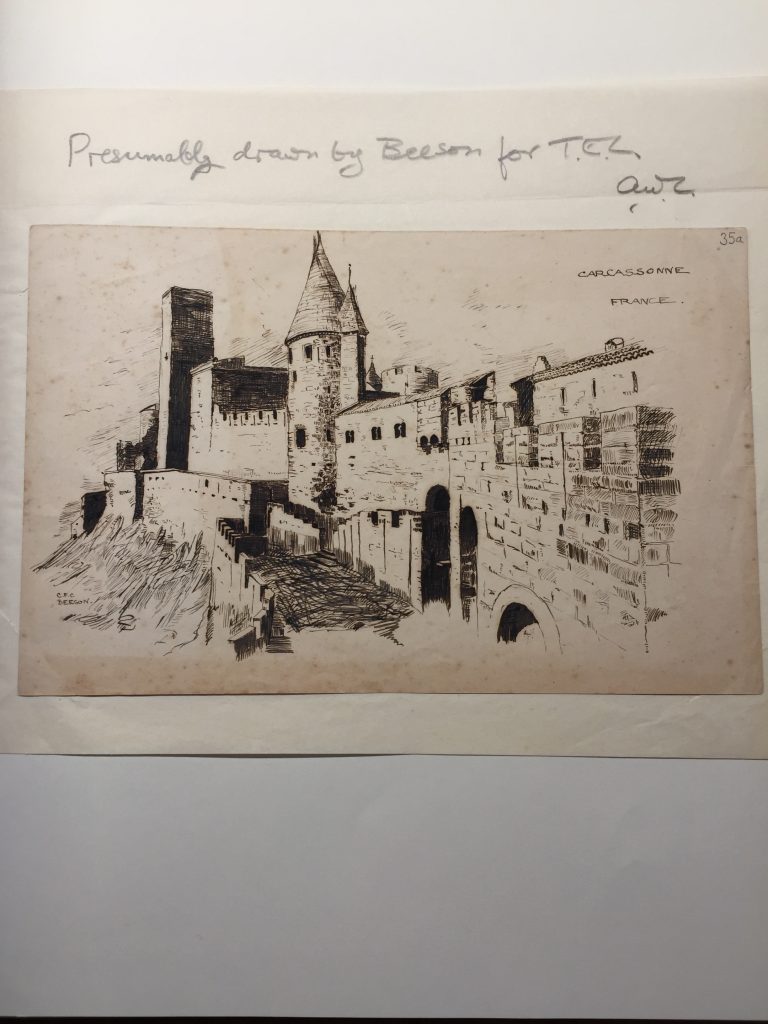

After school both boys went up to Oxford, Lawrence to read history and Beeson to read Geology at St John’s. Despite their Arts/Science difference Beeson and Lawrence remained in touch. Lawrence discovered that there was a rather obscure provision in his degree regulations which allowed him to write an undergraduate thesis and submit it for consideration alongside his compulsory papers. He decided he would write about what had become one of his interests – the history of castles during the crusades. On two long and gruelling bicycle trips across France, Lawrence studied the European castles of the time, and Beeson was there on both occasions to support parts of the journey. Lawrence went on to walk through the Holy Land gathering final material on the castles there before writing his thesis. Time ran short and Lawrence needed help in preparing the illustrations. Once again, Beeson was able to help, drawing numbers of the illustrations, based on photographs, postcards, plans and textbooks such as Viollet-le-Duc’s “Dictionnaire”.

This was perhaps the high point of the association of the two undergraduates. Lawrence, according to Beeson, “had never possessed the average boy’s interest in natural history” and showed little interest in Beeson’s “budding enthusiasm for biology”. After graduation, Beeson embarked on a Diploma course in forestry, while Lawrence started the first of three years as an archaeologist at Carcemish in Syria. Thirty years later Beeson described their last full day together, in the Christmas week of 1908:

“Oxford lay under many inches of snow. We set out to explore its unfamiliarity and, by a route as devious as our conversation, reached the top of Cumnor Hurst in a snowstorm. On the heights the wind blew keenly, sweeping the snow from the domed hill as fast as it fell, piling it in the gloom of the pine-clump or whirling over the cliffs of the brick-pit beyond.”

Lawrence decided that they should return home simply on a compass bearing, and Beeson, faithful friend, dutifully agreed. He writes:

“We held to our compass-bearing, ploughed through snow-banks, climbed hedges and fences, waded icy streams shallow and deep, and were spared the Thames only by the intersection of Folly Bridge and the imminence of night. So finished five years that had reflected one facet of the personality of T.E.Lawrence”

This is a poignant farewell, both to Lawrence and to Beeson’s undergraduate self.

BEESON IN 1922

By 1922, Cyril Beeson was thousands of miles from Oxford. He had gained a Master’s in Forestry, followed by a D.Sc. He had seen war service as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, going through the Mesopotamian campaign. He had married Marion Cossentine Fitze, a Surrey girl, and their only child, Barbara Rose, had been born. He had had a period as a scientist in the field and had been called back to the central offices of his organisation to serve in a senior capacity. He was, in fact, now living and working in India, for the India Forest Service, and the label on his door said “Forest Entomologist”, a position he held for the next twenty years. He was in charge of forest entomology for the whole of India, a country where forest covered 20% of the surface area, and where a nineteenth-century law had brought all of it under the direct control of the British Raj.

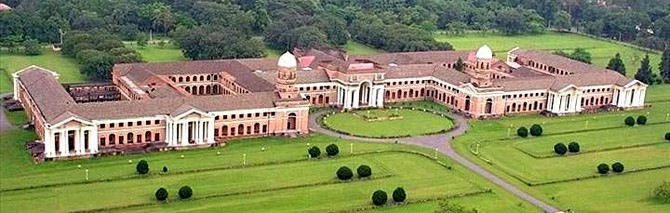

The Forestry Service was a key part of the colonial administration, and Beeson was a Head of Department in its central administration, research and training establishment at Dehra Dun in Uttar Pradesh. These lavish and impressive buildings give an idea of the esteem in which the service was held.

Over the years, Beeson greatly expanded the research undertaken by the department and oversaw the appointment of highly trained, professional staff. This photograph shows Beeson with colleagues.

A huge amount of information on Indian forest insects was produced and published in his time, much of it by Beeson himself in more than sixty scientific articles, and his career was crowned by the publication in 1941 of his book, The Ecology and Control of the Forest Insects of India and the Neighbouring Countries. This 767-page work has been called “the holy book of Indian forest entomology” and remains the standard textbook to this day, having been republished in 1961 and 1993. There are two things to say for the non-expert. First we can see yet again the practical hands-on Beeson in the fact that the volume was actually printed at Dehra Dun, with many of the illustrations are being drawn by Beeson himself. Second, for all that this is the crowning achievement of twenty and more years’ work abroad, the text still shows a characteristic British humour, being interspersed with quotations from Lewis Carrol.

OXFORD AND ADDERBURY

For his services to India, Beeson was made a Companion of the Order of the British Empire when he retired in 1941. On his return to this country, he served as the Director of the Imperial Forestry Bureau in Oxford 1945-7. It was in 1946 that Cyril Beeson moved to Adderbury, taking up residence at Westway Cottage on Horn Hill Road. We don’t know why he and his wife chose Adderbury, but it may have had something to do with their daughter, Barbara Rose. At the end of the Second World War, the twenty-year-old Barbara had found herself in Lagos, and there at some point she met a man from Adderbury, Bennet Humphreys Brackenbury, a colonial administrator. At any event, we next hear of her arriving in Liverpool from Lagos on 7th June, 1949, with the 29-year-old Bennet following on 6th November that year. On 19th November the couple were married at St Mary’s Church, Adderbury.

CLOCK HISTORY

It is said that the first clock that Beeson bought was part of the process of furnishing Westway Cottage. He and his wife thought an antique clock would suit their new home. Once bought, however, apparently they didn’t like its tick, so another was bought. Whatever the truth of this, the death of his wife shortly thereafter seemed to propel Beeson inn two directions. First as collector and secondly as a historian. He was apparently a passionate collector and the obituary in Cake and Cock Horse says that

“those who visited him in his tiny cottage in Adderbury West will remember how its walls were lined with them – longcase clocks, bracket clocks, every sort, on shelves, on the floor, hanging from walls”

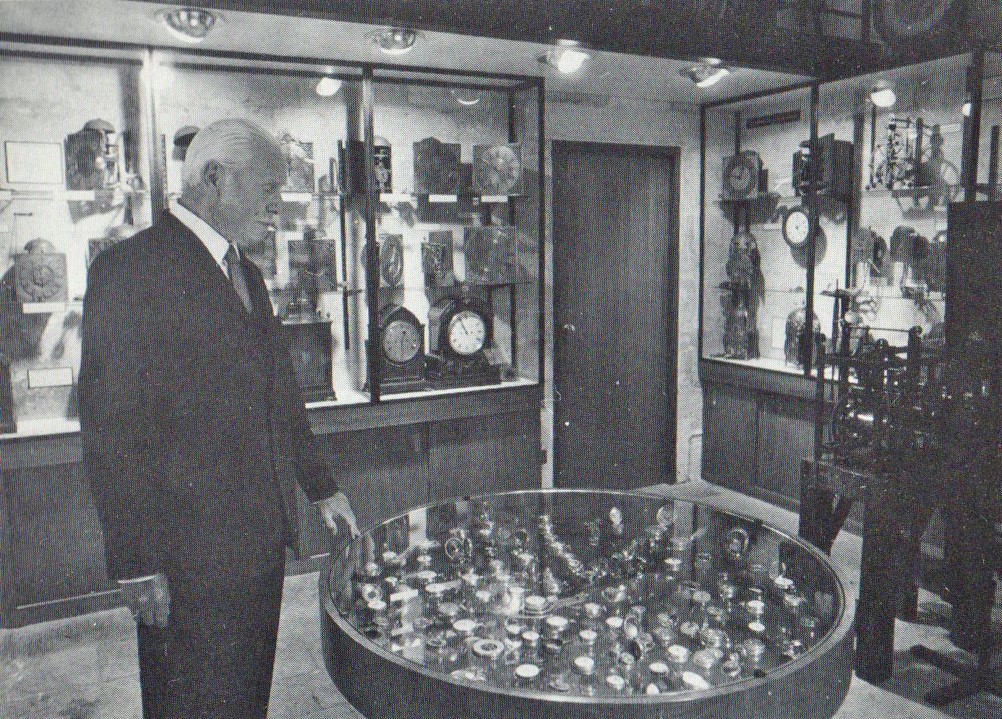

At the same time, he was not the sort of collector who wanted to keep everything for himself. Quite early on, he donated a clock to Banbury Museum, and in 1966 he donated his entire collection, comprising 42 longcase clocks, 24 other clocks and 13 watches, to the Museum of the History of Science at the University of Oxford. The museum created the Beeson Room to house the collection.

In terms of the history of clocks and clock-making, it really is very surprising how little developed the field was in the 1950s and how much progress Beeson made as soon as he turned his attention to it. He first published Clockmaking in Oxfordshire in 1962, and this was followed in 1971 by English Church Clocks 1280 –1850. His final work, Perpignan 1356: The Making of a Tower Clock and Bell for the King’s Castle, was published posthumously in 1982. It is clear that Beeson’s study of clocks was helped by his facility for languages as well as by the fact that he didn’t mind “boldly climbing towers”. But there were two further strengths that Beeson brought to the area. First, he was a scientist, one who was used to classifying huge amounts of data. If we look at this classification of tower clocks, I think we see clearly the same processes at work which had enabled him to make sense of the insect life of Indian forests.

The other strength that Beeson brought to the study of clocks is that he was genuinely interested in history and, in particular, in local history, not just in the technical aspects of clock mechanisms for their own sakes. He joined Banbury Historical Society as a founder member in 1958, was Chairman 1959-60, committee member until 1967, and founding editor of its journal, Cake and Cockhorse from 1959 to 1962 – and it was he, apparently who dreamed up its rather unusual title. He was also a practising local historian, contributing, for example, an article on “Halle Place, Adderbury, and its occupants” in 1960.

Beeson didn’t finish his long life in Adderbury: he married again in 1971 and moved away, his death in 1975 being registered in Abingdon. But in the quarter century he spent here at the end of his life he certainly did more than enough to qualify as a “man of Adderbury”.

Phil Mansell

2020