INTRODUCTION

The Quaker Meeting House in Adderbury was built in 1675 on the estate of the Lord of the Manor of Adderbury West, Bray D’Oyly.

This guide has been prepared to help visitors to appreciate this unique building. It contains some background to life and worship in England in the seventeenth century and an account of how Quakerism arose. Then it tells the stories of the early Adderbury Quakers before giving a guided tour of the exterior of the building and the graveyard, followed by a description of the interior. The guide finishes with a short account of the Quakers of Adderbury from the early nineteenth century up to the present.

LIFE AND WORSHIP IN SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND

Religion played a central role in the life of English people in the seventeenth century in ways that seem very unfamiliar to most of us, looking back from the twenty-first century.

By the time the Quaker story started in the second half of the century, by law you had to attend regularly the services of the Church of England and support its activities by paying to the Church a tithe of either your income or your produce. Religion had in large part lain behind the turbulent national politics of England in the 1600s, which had seen a divisive civil war and the deposition and execution of King Charles I. Religion, too, (particularly in terms of the opposition between Protestant and Roman Catholic beliefs) had determined, and would continue to determine, the international politics of the time.

What is also plain, however, from countless letters and journals of the time, is that at a personal level people thought and felt deeply and intensely about their own relation to God, about their tendency to sin, and about their fitness for the eternal life in heaven which the Christian religion offered to true believers. For many this internal struggle was particularly intense because there was a belief that the Second Coming (when Christ would return to earth in judgement) could happen at any time. As the century progressed it was true for large numbers of believers that the established church did not address their urgent concerns. They began to form themselves into groups and movements that have generally been given the name of “Dissenters”, and prominent among these were the Quakers.

The founder of Quakerism (although it was not called that at that time) was George Fox, who was born in 1624, the son of a Leicestershire weaver. He experienced in full the doubts and confusions described above, and, as a young man, went from preacher to preacher, sect to sect, in search of enlightenment and comfort. As his Journal tells us, it was only when there was “nothing outwardly” left that he found the answer. Then he heard a voice which said, “There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition”; Fox tells us that when he heard this “my heart did leap for joy”. What Fox was proposing was that he and others could learn directly from the living Christ within, the “Inward Light”, needing no priest or minister as intermediary.

Almost immediately Fox, believing that it was God’s commandment that he should do so, embarked upon a missionary crusade, one which was to occupy the remaining forty or so years of his life. He achieved his first successes in North West England but had soon established strong centres in both London and Bristol. From the early 1650s itinerant preachers, known as “Publishers of Truth”, brought their message to the Midlands, and, as far as we know, it was John Audland and John Camm, who visited Banbury in 1654, who first made the contacts, later confirmed on a number of occasions by Fox himself, that established the Quaker connection with Adderbury.

Before we come directly to the Adderbury Quakers themselves, however, a word is necessary about the term “Quaker”. Fox’s co-religionists called themselves the ”Society of Friends” and the term “Quaker” was originally one of abuse, though it was subsequently adopted as a general term. It was in Derby in 1650 that magistrate Gervase Bennet first called Fox and his followers “Quakers”, since they called on men to “tremble at the word of God”. Fox himself was convinced that the “quakings” were the work of God. People’s hearts, he explained, “had to be shaken before the seed of God was raised out of the earth.”

THE QUAKERS OF ADDERBURY

The mission of John Audland and John Camm to Banbury in 1654 must have been a particularly effective one, since their message engaged the attention and won the belief, not only of Edward Vivers, a leading Banbury merchant, but particularly of Bray D’Oyly, the Lord of the Manor of West Adderbury. Both men went on to form Quaker meetings of their own. The first meeting in Adderbury was in 1656 and took place at D’Oyly’s Little Manor in West Adderbury. This still stands, though much altered, on the corner of Cross Hill Road and Colin Butler Green, a short distance from the Meeting House.

D’Oyly’s social position and leadership were very important, since the initial years of Quakerism, from the 1650s to the Act of Toleration in 1689, saw great persecution for Friends, including those of Adderbury. It is hard today to understand why this should be so. Quaker religious practices, for example, seem to us today to be the very opposite of provocative. Martin Greenwood describes these as follows:

“The Friends or Quakers … meet in silence, sometimes called the ‘listening silence’, seeking guidance from the Holy Spirit in their own hearts or through words which individual Friends may feel called upon to speak. The Quaker ‘Inward Light’ linked an individual directly with God, making the prayers and rites of the Church unnecessary. They have no creed, no sacraments, their children are not baptised, they have no consecrated buildings, they do not sing hymns and have no formal prayers.”

Yet these very beliefs brought Quakers into conflict with the established church, for, with their belief in direct guidance from God, they believed in a “priesthood of all believers” and disparaged what they called “steeplehouses” [churches] and their “hireling priests”. They saw no reason why they should attend church services or contribute to church expenses through the payment of tithes, something which infuriated both the clergy and the gentry who made up the magistracy. What is more, Quakers developed a set of attitudes and behaviours that brought them into day-to-day conflict with others. They would not use titles, addressed each other and everybody else as “thee” and “thou”, and refused to doff their hats to anyone, or take off their hats in church, courtroom or private house. All this gave grave offence in the strict social hierarchy of seventeenth-century England. Finally, they would not swear any form of oath, something which time and time again disadvantaged them when they were brought to court. And, of course, seventeenth-century Quakers were instantly recognisable, since the clothes they wore reflected their belief in simplicity, the women in plain grey dresses, white scarves and poke bonnets, and the men in broadcloth with wide-brimmed hats.

D’Oyly was seen by his peers as “a sober and discrete gentleman”, although “wrought upon by these seduced and seducing people [Quakers]”. He himself was fined and imprisoned for attending meetings during this period, but was able to avoid harsher penalties through the good offices of others. D’Oyly was first prosecuted for non-payment of tithes in 1661 and he subsequently refused to pay them right up to his death in 1695. Other Adderbury Quakers were fined and imprisoned for attending meetings either in the village or elsewhere in the county. Thomas Baylis and Christopher Barret were taken at a meeting at Banbury in 1660 and were imprisoned for two months. Members of the Adderbury families of Poultney, Treppas, Aris, and Garner were all fined for being at meetings at Milcombe, Banbury, Adderbury, and Milton between 1660 and 1674. Prosecutions for non-payment of tithes began in 1659 when Timothy Poultney was imprisoned for 15 months. Imprisonment, however, was exceptional after about 1666, but seizure of goods went on until well into the later eighteenth century. D’Oyly played a prominent part in Quaker affairs both at local and national levels. He was frequently appointed to act for the Banbury Meeting in financial matters, or to attend the assizes to look after local Friends who were in trouble with the law.

In 1675, some years before it was legal to do so, D’Oyly built Adderbury Meeting House on his own land and at his own expense. Why was it built? Some suggest that early Meeting Houses were built out of bravado, some that a Meeting House provided simply the opportunity to establish a Quaker burial ground, since Quakers neither sought burial in consecrated ground nor would have been permitted burial there. What is certain is that the need for a purpose-built Meeting House had become more urgent as Quakerism established itself. In about 1668 Fox laid down the organisation of Quaker life, partly as a means of keeping the movement together at a time of persecution. The same basic principles of organisation, however, have persisted to the present day. All Quaker groups at a local level were to hold, in addition to meetings for worship, a monthly business meeting, known as a Preparatory Meeting, which would prepare business for a Monthly Meetings, which concerned themselves with district matters and where each Preparatory Meeting in the area would be represented. Beyond this there were regular regional and national meetings. Importantly, Monthly Meetings were held in turn in all the localities in the district, and a purpose-built Meeting House which could cope with a periodic influx of Friends from elsewhere was a clear advantage. The opening of Adderbury Meeting House was attended by George Fox himself, who stayed with Bray D’Oyly several times, as did Margaret Fell, the organising genius behind the new structure to Quaker life, later to become Fox’s wife. Of one of these meetings, in 1673, Fox’s Journal records ‘ … and thence to Bray D’Oyly’s in Adderbury, in Oxfordshire, where, on First-day, we had a large and precious meeting’.

At Preparatory and Monthly Meetings, Friends were concerned with a wide range of topics. They might discuss, for example, ways of raising money to support either the national cause or local Friends in trouble with the law as a result of the prevailing legislation, or in financial need for other reasons. They might also make enquiries into cases where the conduct of particular Friends was felt to be unsatisfactory, or investigate the background of Friends who wished to get married, or provide reports on the standing of Friends who were intending to move from one area to another within the Quaker organisation. In 1671 George Fox introduced a significant innovation when he required that there be Women’s Meetings held at the same time as the men’s meetings. Men and women had always worshipped together, although sitting separately, but this was the first time that Quaker women were encouraged to be, in Fox’s term “serviceable in their own places and stations”. As a result, they were able to exercise responsibilities within their own religious organisation denied to any other Englishwomen of their time. A contemporary document urged women in their meetings to “administer counsel, wisdom and instruction…to enquire into the necessities of the poor and to relieve the widows and the fatherless and to visit the sick and the afflicted … to reprove the fallen, but mildly … to be teachers of good things … and to be good examples and patterns of prudence.”

With Preparatory Meetings, Monthly Meetings and any follow up that might be needed, as well as two meetings for worship on Sundays and one mid-week, the Quaker way of life must have been quite an all-embracing one. Adderbury’s Quakers were originally in the main farmers and agricultural workers, and particularly, of course, Bray D’Oyly’s estate workers. D’Oyly was so zealous in his support of the movement that the vicar complained in 1682 that whenever houses D’Oyly owned became vacant, he filled them with Quakers from outside the parish and would have no other tenants. This would have been a valuable service to Quakers in nearby parishes such as Broughton, where they were being evicted for their beliefs. In the early eighteenth century the range of Friends’ occupations was increased when Quaker clock-making, first developed in the nearby village of Sibford, came to Adderbury. Richard Gilkes set up his workshop in 1735 and started a tradition which was to last until the death of William Williams in 1862. The clocks made in Adderbury were both highly distinctive, with their zig-zag engraving on the clock faces, and, at least in their simplest form – the “hoop and spike clock” – affordable for the better-off inhabitants. Adderbury customers would also have experienced for the first time the Quaker habit of charging fixed prices for goods. In society as a whole, it was common for purchaser and provider to haggle over the costs of goods or services; Quakers, however, felt that it was a more honest way of working to state a price and to stick to it. Outside the practice of their trade, the clockmakers of Adderbury were throughout zealous and hard-working supporters of the Meeting House.

THE EXTERIOR OF THE MEETING HOUSE

As you turn in from Horn Hill Road and look up the path to the Meeting House on the right, what immediately strikes you is that the building before you is very unlike most other religious buildings. A survey of Quaker Meeting Houses built before 1720 puts it this way:

“No other group of buildings is quite comparable to these plain but dignified and beautiful old Meeting Houses…. Churches are, for example, built to impress… to create awe in the eyes of the beholder [and] … as monuments to the glory of God. They were designed by the best architects of the day. Meeting Houses, on the other hand, were planned for use, for the very practical purpose of shelter in inclement weather. They were in many cases erected by the cooperative labour of the most experienced members of a Meeting, and of course local materials were used, sometimes actually given by the members themselves.”

As a result, of course, a Friends Meeting House is much more like a house in appearance than a church, and it has little or no architectural pretension. It makes no effort to be other than a meeting place, unconsecrated, and sanctified only by the purpose for which it was designed and used.

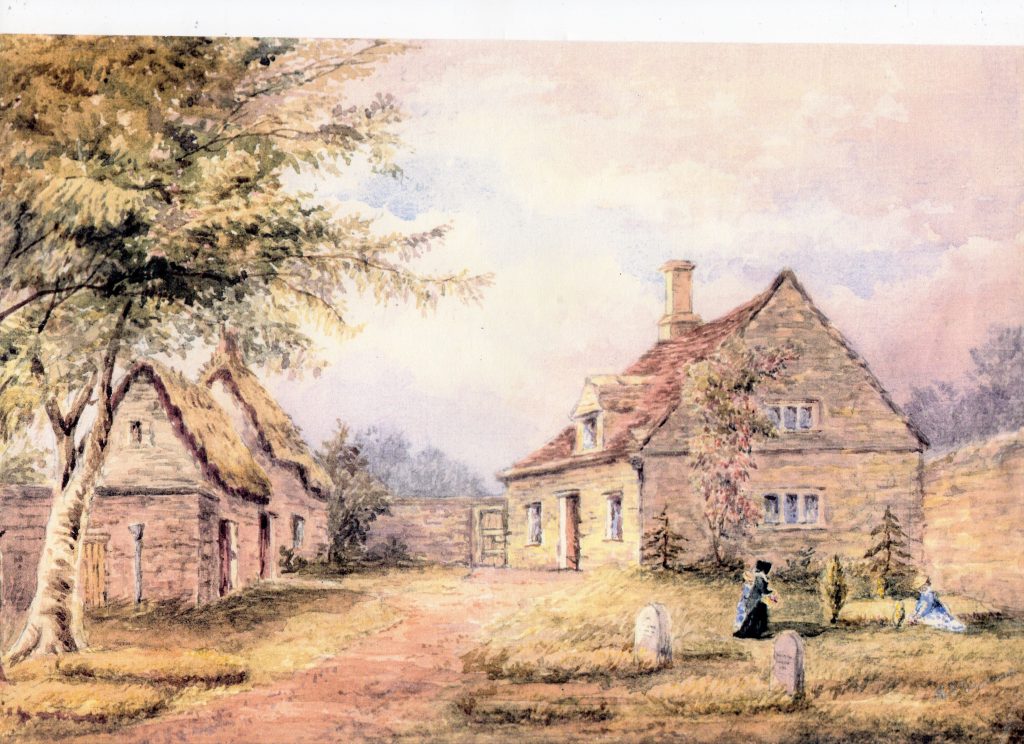

The scene before today’s visitor is, however, considerably changed from the seventeenth century. Where the path now continues past the Meeting House to the Adderbury Parish Cemetery beyond, there would originally have been a wall running across north-south just beyond the Meeting House and closing off the view. And in what is now a sort of empty alcove on the left opposite the Meeting House, a thatched cottage was built in the 1680s, intended for use by the Women’s Meeting, and a smaller cottage which was used to house poor members of the Meeting; the cottages were demolished in the 1950s. In 1954 Adderbury Parish Council took a ninety-year lease on the property, gaining the land to the west of the Meeting House for use as a graveyard and opening up the access. In return, the Parish Council assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the Meeting House. The building was re-roofed with modern slate in the 1970s, but would originally have been covered with Stonesfield stone slates, graded in size from rooftop to eaves. Despite these changes, however, it is clear that at Adderbury, almost uniquely, we have inherited a building largely unchanged in its design since the seventeenth century.

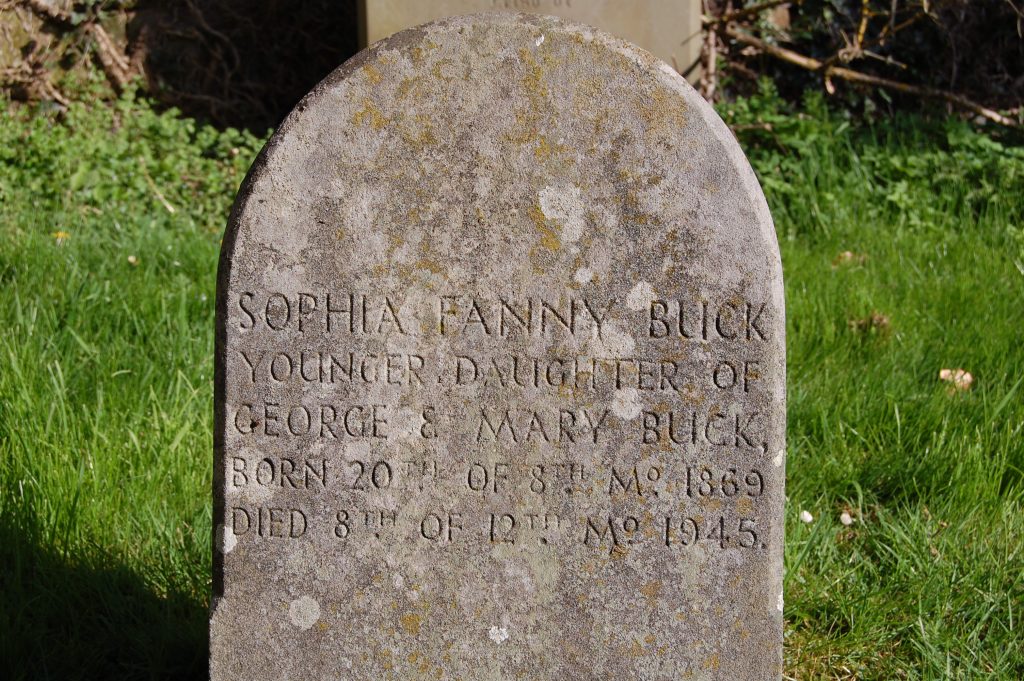

In terms of the graveyard itself, plans show there were some forty graves sited, sometimes three and four deep, on either side of the present path. It was the Quaker habit to level the ground above graves, so that the individual plots are no longer discernible today. The very earliest graves would have had no headstones at all, since at first they were forbidden as a ‘vain and empty’ custom. From 1850, however, Yearly Meeting permitted simple gravestones citing name, age and death date, so as to mark location. The accepted design for generations has been the square-edged stone with a curved top and it is headstones of this type that we now see ranged around the edges of the graveyard. Unfortunately, some of the stone headstones are too worn to permit us to decipher the names. The exception is the headstone of Sophie Fanny Buck, the last Quaker to be buried at Adderbury. Her headstone, recording her death in 1945, can be found on the right, close to the Meeting house itself. It is also easy to read a number of headstones on the left relating to members of the family of the nineteenth-century solicitor Francis Francillon, which still maintain the shape of the other Quaker headstones, but are rather unusually made of cast metal.

Quaker records tell us that no fewer than six Quaker clockmakers are buried here at Adderbury – John Farden of Deddington, died 1786, Richard Gilkes of Adderbury, died 1787, Thomas Harris of Deddington, died 1797, Richard Tyler of Wallingford, died 1800, and Joseph and William Williams, both of Adderbury, who died in 1835 and 1862 respectively.

If we now approach the Meeting House itself, constructed of local coursed square marlstone with some ashlar dressings and wooden lintels, we notice ground floor windows on the east and west sides, with two further windows on the south side flanking the wide front door. It is worth pausing to look at the detailing on the stone carving on the eaves to either side of the front elevation: they illustrate a point made by David Butler, who says:

“Despite the need for simplicity, early meeting houses were not crudely executed. The local craftsmen built as they were accustomed, decorating their work as they knew was needed for a reasonable degree of refinement”

Dormer windows are let into the roof, again on three sides, to provide illumination to the loft area. The date of construction, 1675, is shown in a panel on the chimney, although this feature is not original.

THE INTERIOR OF THE MEETING HOUSE

Quakers needed no altar and their worship did not include music, bible readings or a sermon, the features which give many nonconformist chapels their essential strucrure. This means that Quaker Meeting Houses can seem particularly lacking in architectural features, and this may be the visitor’s first impression of the interior of the Meeting House at Adderbury. Hubert Lidbetter’s history of Meeting Houses tends to confirm this:

“A plain whitened ceiling, plain plastered walls, likewise whitened, over plain deal panelling forming a back to a seat fixed round at least two sides of the room – that is a fair description of an early Friends Meeting House…. The panelling was almost always deal, unpolished and without mouldings … bare necessities and no more – forms or pews of simple design and more than doubtful comfort.”

As we look around it is indeed clear, as the same writer observes, that “the austerity of the Quaker way of living was mirrored not only in their dress and speech, but in their homes and places of worship, where they are enjoined ‘to choose what is simple and beautiful’”.

In the early days worshippers would meet here twice on a Sunday and once on a Wednesday. The times of afternoon meetings would be varied between summer and winter to ensure that they could take place in natural light. Friends would come through the wide front door, the men and women would separate, each to their own side, then take their places on benches, facing a raised gallery or stand against the north wall opposite. The seats here were occupied by elders of the meeting, recorded ministers (Friends whose gifts for ministry were specially recognised by the Meeting) and occasionally visiting preachers or missionaries.

The raised gallery and the seats around the edge of the room, together with the stone flags of the floor are original features from the earliest days of the Meeting House. The free-standing pine benches in the centre of the room have come from the Meeting Houses in Banbury and Sibford. The pillars that support the gallery or loft, the flooring for the loft itself and the roof tiles and the lining of the roof were all replaced in the 1970s. Of the two watercolours on display, one, showing the interior, is a copy of the 1966 original by Mary Baker, which is held at Sibford Meeting House; the other, showing the exterior with adjacent cottages, is an original of 1831.

Tables, like the pleasant eighteenth century one now in the Meeting House, were important in business meetings to enable the Clerk of the meeting to take minutes and draft documents for signature. The predecessor of the present table was venerable indeed, a gate-leg table which was used by George Fox at the opening of the Adderbury Meeting House in 1675. It remained in the Meeting House (together with three coffin stools) even after it was closed to regular meetings in 1914. In 1940, the Meeting House was taken over by the Rural District Council to house wartime evacuees from London. Although, then as now, there was no artificial light or running water in the building, cooking stoves were provided for these families. One day, two local women Friends visited the Meeting House to see how the evacuees were getting on. To their horror they saw someone putting a hot pan on the table and marking it. They promptly replaced it and took the original to the house of Sophie Buck in Church Lane. When Sophie Buck died in 1945, the table was included in her effects and put up for auction. Luckily two Banbury Friends were able to intervene and persuade the auctioneer that the table belonged to the Meeting House, by showing knowledge of that most traditional of things – the presence of a secret drawer, containing ink and a pad of Quaker forms! The table is now in Swarthmoor Hall in Cumbria.

The ground floor of the Meeting House (area 561 square feet) was designed to seat 102 Friends. The Meeting House would rarely have seen more than this number, but if further seating was needed, there was space for a further 60 attendees in the gallery or loft above, reached by the curving staircase on the left of the main room. The design of the loft at Adderbury is unusual, because so much of the upper area is floored in, leaving effectively only a well over the stand occupied by the elders. The reason for this is apparent from the first space we come to at the head of the stairs, since it is almost domestic in character, with, very unusually for early Meeting Houses, a fireplace. In fact, this was used for the women’s meeting. As is quite common in early Meeting Houses, the space could be rendered quite private either by mounting screens or by using a curtain or hanging to separate this area from the main Meeting House area below. In time, the space became too small for this purpose and, as we have seen, a separate building had to be provided. On one windowsill is now displayed the original exterior date plaque of 1675.

As you take in the atmosphere of this building with what the architectural historian John Summerson called its “endearing simplicity”, you may like to hear some Quaker voices of the past. First comes an account from Robert Barclay, like Bray D’Oyly a Quaker convert from the gentry, written in 1678, only three years after this Meeting House was built, of what you could expect to experience in a Quaker meeting in those very early days:

“There will be such a painful travail found in the soul, that it will even work upon the outward man, so that … the body will be greatly shaken, and many groans, sighs and tears …. Sometimes the Power of God will break forth into a whole meeting … and thereby trembling … will be upon most … which as the power of truth prevails, will from pangs and groans end with the sweet sound of thanksgiving and praise.”

Secondly, we can imagine, by contrast, a business meeting in the eighteenth century, when the evangelical years of George Fox were over. Much of the activity of Monthly Meetings at that time was taken up with the enquiries which were deemed necessary when a Friend moved away and wished to join another Monthly Meeting, or wished to get married, or on issues of general conduct. Here is a typical Minute:

“From our Monthly Meeting held at Adderbury for Banbury Division in the County of Oxford. To the Monthly Meeting of Friends to be held at Campden or elsewhere in that Division of the County of Gloucester. Dear Friends, whereas Elizabeth Franklin, a member hereof, but is now removed into the compass of yours, a certificate has been requested of this meeting on her behalf. Therefore, this may certify, after due enquiry being made, it appears she was of sober life and conversation, and free from marriage entanglements. As such, we recommend her to your tender regard ….”

Finally, since the Adderbury Meeting House is still used for Quaker worship, here is an account of a contemporary Quaker meeting for worship:

“A Quaker meeting creates a space of gathered stillness. We come together where we can listen to the promptings of truth and love in our hearts, which we understand as rising from God. Our meetings are based on silence: a silence of waiting and listening. Most meetings last for about an hour.

The silence is different from the silence of solitary meditation, as the listening and waiting in a Quaker meeting is a shared experience in which worshippers seek to experience God for themselves. The seating is usually arranged in a circle or a square to help people be aware of one another and conscious of the fact that they are worshipping together as equals. There are no priests or ministers.

The silence may be broken if someone present feels called to say something which will deepen and enrich the worship. Anyone is free to speak, pray or read aloud if they feel strongly led to do so. This breaks the silence for the moment but does not interrupt it.

In the quietness of the meeting, we can become aware of a deep and powerful spirit of love and truth, transcending our ordinary, day-to-day experiences. This sense of direct contact with the divine is at the heart of the Quaker way of worship and nourishes Quakers in the rest of their daily lives.”

ADDERBURY QUAKERS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ONWARDS

The story of the Adderbury Quakers from the death of William Williams, the last Adderbury clockmaker, in 1862, to the end of the nineteenth century is unfortunately one of continuous decline. In this, the Adderbury meeting was partly sharing the fate of Quaker congregations nationally; as one study starkly puts it:

“While the population of England had trebled between 1715 and 1851, the number of Quaker adherents had more than halved.”

One cause of this decline in numbers related to the rules that prevented Friends from marrying outside the Quaker community, and the Quaker movement began to relax these restrictions. But in Adderbury, there was the additional problem of agricultural decline. An 1806 report says:

“Almost all the Quakers were originally in the country … but this order of things is reversing fast. They are flocking into the towns and abandoning agricultural pursuits.”

Attendances at Adderbury meetings had shrunk to an average of 12 in 1851, were down to 4 by 1909 and the Meeting House closed in 1914. One remaining Adderbury Friend, however, Sophie Fanny Buck, whose gravestone we have already seen, continued her personal worship at the Meeting House, something she did, frequently wearing traditional Quaker dress, until her death in 1945.

Paradoxically, as local and especially rural numbers declined, so the reputation of Quakerism grew on the national stage. Their honesty and fair dealing in business and trade was even more appreciated as Quaker firms such as Fry and Cadbury became of national importance, Quaker probity played an important role in banking and insurance, and the Quakers’ long-standing pacifism gained increased respect. Quakers were involved in adult education as well as in evangelical work abroad and charitable activities at home. A Quaker residential home for the elderly, East House, was maintained in Adderbury from the late 1960s until its closure in 2008.

The Adderbury Meeting House is currently (2014) used for Quaker meetings four times a year, with a special meeting once a year which takes the form of a lecture on a Quaker theme of general interest. There has been considerable debate of recent years about the best way to secure the future of Adderbury’s historic Meeting House. We hope that the present Guide will at least help to alert people to the important part of the village heritage that the Meeting House represents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This guide has benefited from the following works on Quaker Meeting Houses generally: David M. Butler (1995), Quaker Meeting Houses, Quaker Tapestry Booklets; Hubert Lidbetter (1961), The Friends Meeting House, William Sessions Ltd., York; Kenneth H. Southall (1974), Our Quaker Heritage: early meeting houses, Friends Home Service Committee in association with Sessions of York. In addition to the standard histories of Quakerism and Dissent generally, we have found the following local studies particularly useful: Nicholas Allen (2012), “The Doylys of Adderbury and their Quaker Meeting House, Cake and Cock Horse, Spring 2012; Martin Greenwood (2013), Pilgrim’s Progress Revisited: The Nonconformists of Banburyshire 1662-2012, The Wychwood Press; Jack V. Wood (1991), Some Rural Quakers, William Sessions Ltd., York. We are grateful to Nick Allen for encouraging us to write this guide, for supplying material and for guidance throughout its writing. We would like to thank Janice Johnson for agreeing to read the manuscript and for suggesting improvements. Any remaining errors are our own.

Phil Mansell

Fiona Gow