When I see a large crusty loaf in a shop window I always remember our local bake house that I used to visit as a child. On Sunday mornings my father, carrying a large baking tray containing our Sunday dinner, would leave me at the door of the Chapel Sunday School, then go further down the lane to the baker’s. After Sunday School we younger ones were required to attend the first half of the chapel service: we were allowed to go home before the sermon.

Dad would be waiting with several Sunday newspapers he had purchased from a builder’s yard on the way to meet me. There was no Sunday delivery so the local builder had the papers left at his yard for collection. We would take them to Aunt Hannah and Aunt Eva; they were really my Dad’s cousins, but I called them “Aunt” as we were not allowed to call adults by their Christian names then. Maybe Dad would have brought some vegetables or some of Mam’s jam. They would find something for us, perhaps a cake or some home-made wine. That’s how it was then.

Soon Dad would say it was time to go back to the bakehouse, where a lot of people would be waiting, laughing, joking and catching up on each other’s news. Suddenly, all would go quiet and Mr Wallin and his son would appear wearing long white aprons. As they opened the door of the big oven, the whole place would be filled with a wonderful aroma from the beautifully cooked joints, each one resting on a trivet with a large, thick Yorkshire pudding underneath. The baking tins would be skilfully brought out of the oven with a long-handled wooden shovel called a peel. In no time at all the dinners had been claimed, covered by a white cloth, and hurried home before the contents got cold. On occasions, somebody would take the wrong one; this happened to Dad once and I remember that he put a couple of split rings on the handle of the baking tin so that he could recognise which one was ours. This procedure had gone on for many years, but faded out when in 1933 the electricity came to the village.

Although the baker delivered three times a week, there were still times when we needed to visit the bakehouse on weekdays. It was a lovely place, smelling of newly-baked bread, dusty and warm. There was a large metal drum for mixing the dough. The flour would come down a cloth chute from a loft into the drum. Mr Wallin was very kind and would tell us to stand well away so that we didn’t get the dust in our eyes. When there was the right amount of flour he would tie the chute in a knot to keep it out of the way. Then he would tip in the frothy yeast liquid and lock the lid on very tightly. To mix the dough, the drum had to be turned with a handle at the side. This would have been very hard work. Later they were able to instal an electric motor to do the job.

Three men, two of them the baker’s sons, might be standing at a bench kneading the dough that had been put to rise in a large wooden trough. They worked like clockwork, pulling the dough forward with their hands and pushing it back with their forearms. When the dough was ready, it was cut into pieces, weighed, and put into tins, or if they were making my favourites, cottage loaves, they would be put onto flat trays.

I was always sorry when someone had time to serve me, as I would have like to stay all day. Sometimes I would be lucky enough to be there when the bread was brought out of the oven. They had a long, hinged gas pipe which flared at the end when lit and could be pushed right inside the oven so that the men could see to reach the loaves, as the oven went quite a long way back. Often, if was sent to get a cottage loaf, I would lift the top slightly so I could get some nice soft pieces out to eat on the way home. One day, my Dad said he would have to see Bern Wallin about his bread. “He must have got a mouse”, he said. “This bread has got a hole in it.” I expect he knew it was me.

During the war the flour was not so white, which made the loaves a darker colour, although the Ministry of Food said it was better for us. At that time, too, the baker made powder cakes, a rather dry fruit cake, but things were scarce and it went down fine with some of our tea ration. We also bought our toppings from there to feed the chickens and sometimes bran for the pet rabbits. During the war you had to apply for a card to buy meal if you kept chickens.

After the bakehouse closed and Mum started to buy “shop bread”, as we called it, my Dad would complain that it had no crust. “It’s not baked now, it’s boiled” he would say. I often wonder what he and Mr Wallin would think of today’s microwaves and such like.

Rhoda Woodward

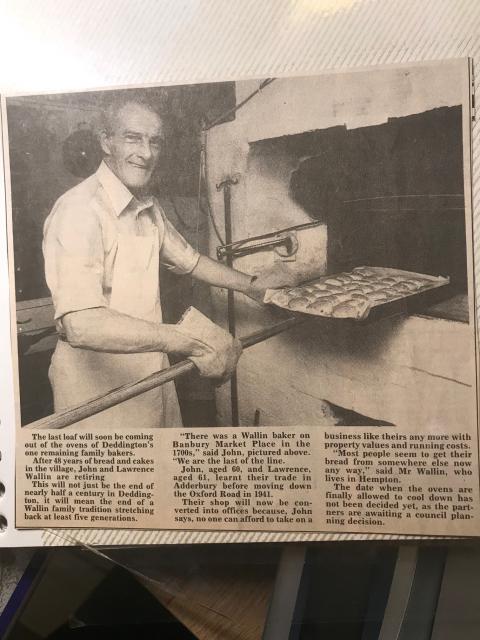

Note: Mr Wallins’ sons. John and Lawrence, who Rhoda watched kneading bread before the war, moved to Deddington in 1941 and set up their own bakery there. This continued in business until 1989, when the Banbury Guardian announced the closure of the bakery.