William Cole was brought up in Adderbury from birth to the age of sixteen, a son of the local schoolmaster. He remains of interest to us today because in his twenties he became “the most famous simpler of his age”, a simpler being a herbalist. This is quite some claim, given that William Cole was an almost exact contemporary of a herbalist much better known to us today, Nicolas Culpeper.

The claim about William’s fame comes in a volume compiled by Anthony Wood (1632- 95), called Athenae Oxoniensis [roughly, the Oxford Athens], in which he set out to provide biographies of all the writers and bishops who had received their education to date at Oxford University, documenting the lives and publications of over 1500 writers associated with the University, creating an indispensable record for historians.

This huge work went alongside other books of his which charted the history of the university, its colleges and officers, and which described the university’s buildings. Wood’s work was published in the 1680s. He has been described as “to Restoration Oxford what Pepys was to Restoration London”, although the two men were very different in character, with Wood being a cantankerous and vituperative character who fell out with everyone sooner or later.

This is what Wood has to say about William Cole:

“William Cole, son of Joh. Cole of Adderbury in Oxfordshire bach of div and sometime Fellow of New College, was born and educated in grammar learning there, entered one of the clerks of New College in 1642 and soon after was made one of the portionists commonly called post-masters of Merton Coll. By his mother’s brother John French one of the senior fellows of that house and public registrar of the University.”

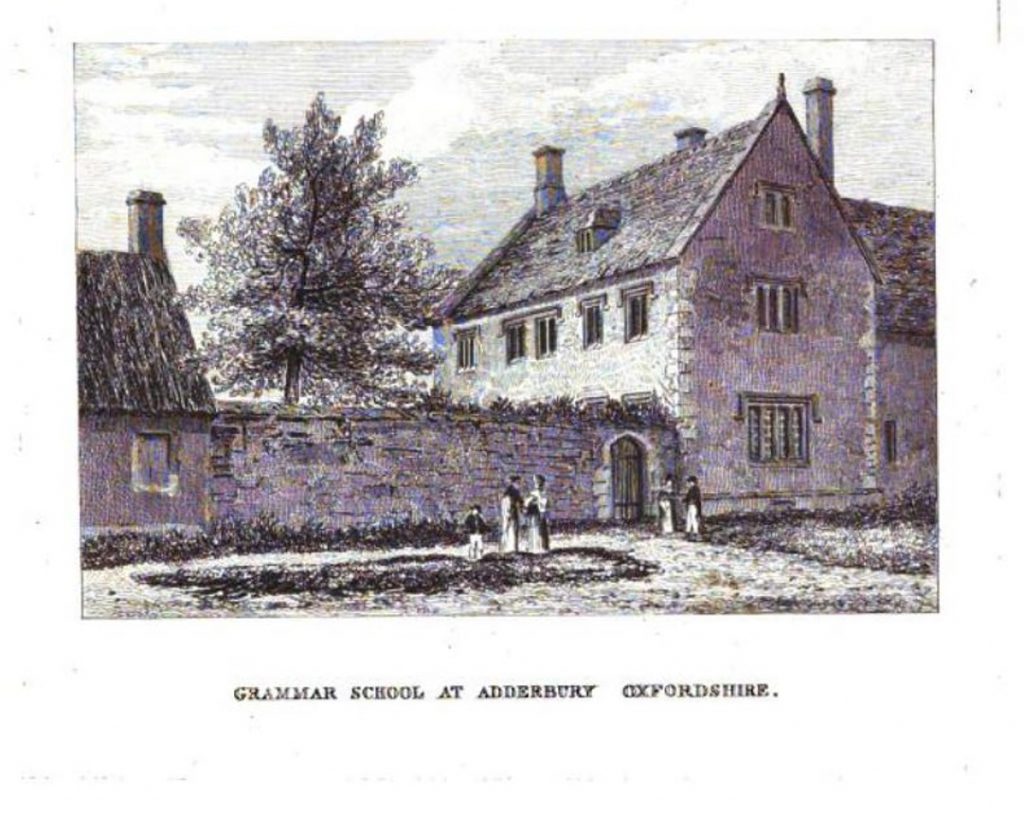

Wood also mentions the older brother of William, called John after his father, who was born about 1624 and who went on to make a reputation for himself as a translator of French. The Dictionary of National Biography indeed says that William was one of at least three sons and five daughters of John Coles. John the father was a bachelor of divinity and one of the three seventeenth-century Adderbury grammar school masters who were university graduates. He is remembered for having been particularly zealous about the building and its repair. William’s mother’s maiden name was French, and since John Cole senior’s predecessor as master was also called French, the possibility exists that William’s mother was a daughter of this French. As far as we know, the Cole family lived in the school house, part of the grammar school building. The whole was described by Warden Woodward in 1659 as “nothing but a Schole, a Schoolehouse & about 6 or 7 roomes above staires … A Barne built by one Mr. Coles, a Little court before the doore etc.” The rooms above, Warden Woodward judged, “might be made good, one of them doth want fflooreing!”

We can assume that the accommodation for the master and his family was not particularly spacious, since a later schoolmaster, Mr Taylor, made an unsuccessful bid for some common land to build a house on. Nor can we imagine that the schoolmaster was particularly well paid. The same Mr Taylor asked that his wages be paid to him quarterly rather than half-yearly “the better to maintain his family”. This was refused on the grounds that Christopher Rawlins had specified both the amount and the timing of the payments to the master – namely “Twentie Nobles at the Annunciation & Twentie Nobles at Michaelmas”.

Wood says that William was “educated in grammar learning” at the School and then proceeded to New College as a clerk. These words would have had a meaning for Wood’s audience which we can’t catch nowadays. The “grammar learning” would, of course, have been had at the Boys School, founded and endowed by the vicar of Adderbury, Christopher Rawlins, in his will of 7th August, 1589, opened in 1599 and hence only some thirty years old when William was a pupil. The purpose of the school was to teach grammar to boys who had already had some elementary education, since all scholars were expected to read, write and cast accounts to gain entry to the school. Nick Allen, in Adderbury, A Thousand Years of History, tells us about the curriculum and the rules of conduct for the school, basing his account on the archives of New College, which was from the outset responsible for the administration the of the school.

“The education given at the Boys School was comprehensive, giving the boys a good grounding in the basics… By the time a boy was 12 … he should have been [in addition] instructed in religious knowledge, Church of England liturgy, higher rules of arithmetic , the rules of simple compound numeration (fractions), writing from dictation and memory, multiplication tables and the outlines of geography. When a boy was due to leave the Boys School he would also have studied the outlines of ecclesiastical history, Latin, English grammar, composition, algebra, mapping, mental arithmetic, bookkeeping, penmanship and mensuration.

Several sets of rules for the conduct of the Boys School are still extant … A summary of one of the earliest sets, dated between 1648 and 1658, states: ‘That the hours shall be from 7 am to 11 am and from 1 pm to 4 pm. Each morning boys are required to say a prayer, a psalm and a collect, and another prayer and collect at the end of the day. Saturday afternoon to be given over for the teaching of the Catechism. Scholars are expected to attend Church on Sundays and behave in an orderly manner.”

Once William entered New College in 1642 he came under the influence of his uncle, John French, who was a senior member of Merton College and Registrar of the University. John French obtained for William a post of “Portioner” or “Post master” at Merton College, a position which apparently attracted a grant from the college. French also encouraged William to qualify as a public notary, so that William would be able to stand in for John as University Registrar. By all accounts the support of a bright youngster, especially one indebted to you, would have been welcome to John French, because elsewhere Wood says of him that, although he was a fine scholar “he was a careless man” and neglected some of his duties.

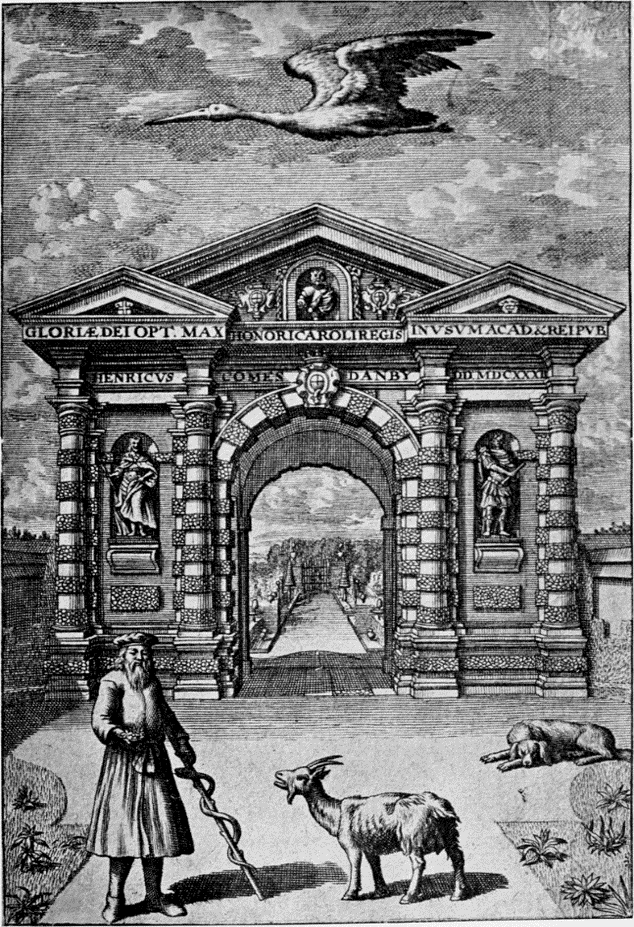

At the same time William became interested in biology and botany. This was the time when Jacob Bobart was gradually forming the first University collection of plants in the new Physic Garden, the catalogue of which was produced in 1648. When he eventually came to publish his own botanical studies William would acknowledge the help he received from “Master Bobart” and particularly from his “much honoured friend” Master William Brown of Magdalene College (1629-1678). Brown eventually had a very distinguished academic career at Magdalene, but in the 1640s was known for his keenness for field botany, ranging widely over the Oxford region and as far afield as Northamptonshire and Sussex in search of plants.

So far so good, you might think, for the young man from Adderbury. But then in 1650 things began to go disastrously wrong. First, his uncle died and was buried by his stall in Merton College Chapel. Then, if you like, the elephant came into the room. Because the 1640s were not the simplest or most auspicious time to be up at Oxford. This was the time of the first Civil War and Oxford was a royalist stronghold and the headquarters of the King’s forces, – and the dwelling place of the King and Queen and their household.

After the execution of King Charles I and the end of the first Civil War, Parliament turned its attention to Oxford and to its troublesome University in particular. Parliament set up a Commission, and the Commisssion was charged with asking all at the University two questions:

- Do you acknowledge the supremacy of Parliament over the (previously autonomous) University

- In your personal and communal worship will you follow the precepts of the Directory of Public Worship

The University tried to ignore the Commission, a strategy which worked quite well at first, but eventually Parliament would not be denied and there were wholesale expulsions, with staff replacements drafted in from other universities. New College fared particularly badly, with the Warden, forty fellows and numerous scholars expelled, William Coles included.

William acted quite swiftly, it seems. He took his degree in February 1651 and later that year withdrew from Oxford, moving to live instead downstream at Putney. Why he chose Putney is not clear – there doesn’t seem to be a New College connection, for example. But if we take William to be a royalist, a traditionalist in religion and a scholar deeply interested in botany, then we may be able to make some guesses. First, there were a number of important Royalist sympathisers who lived by the banks of the Thames to the ewst of London. The most important was Christian, Duchess of Devonshire. So active was she in the Royalist cause and so seemingly immune from prosecution as a result of her great wealth and willingness to bribe every court in the land that she soon became almost synonymous with the Royalist cause. General Monk is said to have informed her in advance of his intention to return Charles II to the throne.

The other inhabitant of the Putney/Richmond area at the time was Bishop Duppa, another staunch Royalist, a great favourite of Charles I, and tutor to the future Charles II. Duppa was deeply involved with the King in the run-up to his execution, and read the text of a publication, “Eikon Basilike” to Charles at Carisbrooke Castle. This text was later published only ten days after the King’s execution, and, written as a diary in a simple, moving and starightforward manner aims to show a “Portraiture of His Sacred Majestie in his Solitude and Sufferings”. Despite official disapproval, the work was hugely popular.

Duppa’s life had been involved throughout with Oxford, the King and the Laudian Church of England. He had been a fellow of All Souls, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1632, Dean of Christ Church, Chaplain to Charles 1 from 1634 and tutor to his two sons, Bishop of Chichester 1638 and Bishop of Salisbury from 1641. Uniquely in Cromwellian England he held on to his bishopric throughout the 1640s and 1650s.

One of the reasons for Duppa’s survival may well be that he lived as much as possible out of the public eye. It is interesting to read the words of a letter he wrote to a friend in the early 1650s, because of the picture they give of the trials of everyday life in the Royalist camp if you didn’t have the prestige and resources of the Duchess of Devonshire. It may well be that we also hear in this an echo of what life was like at that time for other royalist sympathisers and traditionalists in religion, not least, of course, for William Coles.

‘I wrote you word in my last that I had confined my self like an anchoret within my own walls, but this being not under the religion of a vow, I was the very next day drawn out by the importunity of friends as far as Fulham; and it was well that I was not out of the compass of my circle, for the evill spirits were abroad that day, and seeking whom they should devour, seas’d upon som guilty of my faults, loyalty, and religion.

But I thank God, having considered all things, I have sett up my rest, and

whether I escape, or suffer, I hope I shall keep that evenness of mind, as to be aequally affected to either… yet I shall strive to be so much a Christian, as neither to please nor displease myself too much with whatsoever shall happen. Those few words, “Thy will be don,” settle the soul more than the loadstone can possibly operate upon the needle…’

‘I could heartily wish (if the conditions of the times might give you leave) that you fill’d a room among us, but how wide soever the lines of the circumference may be, yet meet they shall in the center. We are yet suffer’d to offer up the publick prayers and Sacrifice of the Church, though it be under private roofs, nor do I hear of any for the present either disturb’d or troubled for doing it. When the persecution goes higher, we must be content to go lower, and to serve God as the antient Christians did, in dens, and caves, and deserts. For all the world is His chapel, and from what corner of it soever, we lift up our devotions to Him, He is ready to listen to the lowest whispers of them.’

Looking at William’s move from the point of view of his biological interests, it seems probable that from his base to the west of London he took advantage of the expertise of William How, who William refers to as “Doctor How, one of the masters of the Physick Garden at Westminster”, the forerunner of the Chelsea Physick Garden, “one of the most famous botanists of my time”. William How had been born in 1620, went to Merchant Taylors’ School, graduated BA and MA from St John’s College, Oxford, then entered on the study of medicine. This he interrupted to take up arms in the king’s cause, and for his loyalty was promoted to the command of a troop of horse. On the decline of the royal fortunes he resumed his medical profession, and practised in London until his death in 1656. Howe published among other titles Phytologia Britannica (1650), which is the earliest work on botany restricted to the plants of this island, and is a very full catalogue for the time.

No doubt with How’s support and with help of How’s gardener at Westminster, William Coles himself produced the two works which led Wood later to call him the “greatest simpler of his age”. In 1656 he produced The Art of Simpling, or an Introduction to the Knowledge and Gathering of Plants, London, while in 1657 appeared Adam in Eden, or Nature’s Paradise. The full title of the second book gives a clear idea of the contents, and of why the books would prove to be popular, giving as they do a guide in English through the often confusing terminology typically used in scientific textbooks:

Adam in Eden, or, Natures paradise, the history of plants, fruits, herbs and flowers with their several names, whether Greek, Latin or English, the places where they grow, their descriptions and kinds, their times of flourishing and decreasing, as also their several signatures, anatomical appropriations, and particular physical vertues, together with necessary observations on the seasons of planting, and gathering of our English simples with directions how to preserve them in their compositions or otherwise … For the herbalists greater benefit, there is annexed a Latin and English table of the several names of simples, with another more particular table of the diseases, and their cures, treated of in this so necessary a work /by William Coles …

William’s books were immediately popular and remain so today. The Art of Simpling, for example, went through six editions in its first year, and saw eighteen further editions between then and 2000. Adam in Eden went through 20 editions between 1657 and 1962. In the face of these sorts of figures we must suppose that it was his publishing activities that supported William Coles during this period.

Unfortunately for William’s reputation as an academic and scientist, however, as soon as he turned his attention away from the practicalities of the gathering and use of herbs, and considered instead the biological and botanical theory behind the practice, William showed himself to be rather traditional and backward-looking, relying on classical and medieval theories rather than taking part in the growing rational and scientific debate that would see, for example, moves to establish the Royal Society from 1660 onwards. Indeed, William was happy to look for theological rather than scientific explanations. He believed that God created the world for man’s benefit, and that God gave plants particular attributes from which we can deduce the use to which they can be put in medicine. This is known as the Doctrine of Signatures. In the words of William himself:

“The mercy of God which is over all his workes…hath not onely stemped upon them (as upon every man) a distinct forme, but also given them particular signatures, whereby a man may read even in legible characters the use of them… Hounds Tongue hath a forme not much different from its name which will tye the tongues of houndes so that they shall not barke at you…”.

In other words, he believed that herbs resemble various parts of the body and can be used to treat ailments of that part of the body and do so deliberately as part of God’s mercy to man. Thus, walnuts were good for curing head ailments because in his opinion, “they Have the perfect Signatures of the Head”. Regarding Hypericum, he wrote, “The little holes whereof the leaves of Saint Johns wort are full, doe resemble all the pores of the skin and therefore it is profitable for all hurts and wounds that can happen thereunto.” The doctrine of signatures is ancient, going back at least to the time of Dioscurides and Galen. But it was William Coles who gave the fullest account of this in modern times.

So, as the 1650s go on, we have William Coles, a successful author of popular science, but not one of the new breed of scientist who would shortly establish the Royal Society. 1660 came, and with it the restoration of the monarchy. Bishop Duppa benefited almost immediately, becoming in that year the Bishop of Winchester, the third most important see in the country after the archbishoprics of Canterbury and York as well as Lord Almoner. And who should be appointed his Secretary in the same year? No other than the man from Adderbury, William Coles.

This is not quite the happy end you might imagine, however, since both Duppa and Coles only lived another two years, both dying in 1662. Such was the importance to the new King, Charles II, of Duppa, his old tutor and the confidant of his father, that, learning of Duppa’s final illness, the King came himself to Winchester to kneel at the feet of the bishop and ask his blessing before he died. It would be good to feel that William Coles lived at least to see this extraordinary scene and that he gained some comfort from the fact that the world as he saw it had resumed its right course after the troubles of the 1640s and 1650s.

Phil

Mansell

May 2020