When it was completed in 1790 the Oxford Canal provided a vital link between the industrial Midlands and the markets of Oxford and London, and completed the “Grand Cross” of waterways intended by James Brindley and others to provide the transport infrastructure for the Industrial Revolution. The canal was initially very successful, but later suffered a long period of decline as a commercial waterway. During the two hundred years of changing fortunes, what was the relationship between the Canal and the Parish of Adderbury East, through which it makes its way from Banbury to Oxford?

Basics

By the time the final section of the Oxford Canal, from Banbury down to Oxford, was started in the 1780s, the need for completion of the route was urgent. The canal had reached Banbury twelve years before, but had then run out of money. However, with a new Parliamentary Act in place allowing for the raising of new capital, a new man in charge and innovative arrangements for completing the work on time, the work was finally begun in 1788.

The work still had to be completed as cheaply as possible, and the extension to Oxford continued to be planned and built as a “contour” canal, following the contours of the land until a change of level, and the building of a lock, was absolutely necessary. This, and other cost-saving decisions involving sharing water in various ways with the River Cherwell, meant that Adderbury was never going to be a “canal village”, like Lower Heyford or Thrupp, since the line of the canal was in the Cherwell valley, some distance downhill from the village centre. Points of contact would be hence at all periods limited to the three wharves in the parish with road access, and to the various industrial wharves along the stretch.

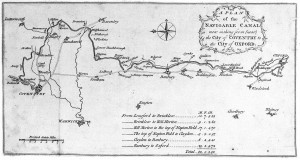

The original map of the course of the Oxford Canal

The original map of the course of the Oxford Canal

The canal enters the parish from the north below Grant’s Lock, passes a canalside complex and road bridge at Twyford Wharf, a lockside ensemble at Tarver’s Lock, and a lock and wharf complex at Nell Bridge before leaving the parish a short distance to the south at Weir Lock. Among the most obvious archaeological remains are the numerous “lift bridges”, designed to provide a cheap means of access for farmers where the canal had divided their fields.

A lift bridge near Nell Bridge

Initial Contacts

When the canal arrived, the social and economic structure of the village of Adderbury was focussed almost entirely on agriculture. Within this community, the landed aristocracy saw the canal primarily as an opportunity for investment, while small farmers experienced it mainly as an unwelcome intrusion. There was provision made for their need to access their fields, but there was a widespread feeling that the building of the canal had done no good to the land, a feeling that is probably behind the view expressed in Young’s 1809 Survey of Oxfordshire that “a very large tract of valuable meadow land on the banks of the River Cherwell has been much injured and in many cases spoilt by a navigable canal … from Banbury to Oxford very ill executed.” Once the canal was in operation, a petition of 1811 by landowners to the canal company shows that farmers felt that they had “sustained various injuries and depredations from the navigation of the … canal” and requested that the towing path be fenced off from adjoining fields.

A third group of Adderbury residents, the agricultural labourers, seem to have been by and large unaffected by the advent of the canal. It used to be thought that the labour to build the canals anywhere in the country must have come from the land, with agricultural labourers attracted by much higher wages. However, not only is there no evidence for this happening to any significant extent here or elsewhere, but we also now understand much more the role of contractors in canal-building. If a potential “navvie” wanted to be taken on by a contractor, then he had to show himself to be not just hard-working, but adaptable and quick-witted as well and used to operating as part of a team. It’s likely that men who already had experience of contract work, on the canals themselves, on the turnpike roads, or even in landscape gardening, would be preferred.

The advertisement for labourers on the Southern Oxford Canal, 1788

The rest of late eighteenth century Adderbury was made up of those providing goods and services for agriculture or just daily necessities, or those engaged in cottage industries. There was certainly plush weaving in the village and possibly lace-making, and it may be that the numbers of bootmakers, maltsters and fellmongerers locally also point to trade that went beyond the village. Yet in all these cases it is unlikely that the advent of the canal offered anything not already provided by traditional transport and patterns of local delivery and collection.

Benefits of the Canal for the Village

When it was finally operational, of course, the canal did change the life of the village in important ways. It brought cheap coal to an area which had previously been notorious for the absence of fuel; it was a convenient means of bringing road-building, road-mending and house-building materials to the village; it provided direct employment and stimulated canalside industries; and it possibly gave a fillip to the sale of agricultural produce.

The wharves and locks in Adderbury parish itself provided work for Adderbury men. The wharfingers looked after security at their wharves, ensured that boats calling were dealt with in a sensible sequence, made sure that goods awaiting collection were properly stored and enforced the canal company’s rules. Despite the fact that they were the best paid, wharfingers frequently combined their role with that of landlord of a canalside pub and coal merchant for the village. The lock-keepers had a more restricted role, which they combined with that of general canal labouring. Censuses also show Adderbury men at various points in the nineteenth century working as labourers on the canal as a whole.

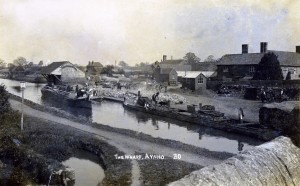

A canal wharf at nearby Aynho

The canal probably stimulated growth in the pre-existent brick and tile works at Twyford and may have been the impetus for newer enterprises of this sort in the Nell Bridge area. There is a noticeable growth in limekilns along the length of the canal, suggesting the export of fertiliser. Most histories suggest that farmers sought to export their produce in search of higher prices elsewhere, but this was very unpopular, especially at times of food shortages and gave rise to civil unrest in Banbury, Oxford and nearby Aynho. In the early days of ironstone mining in the Aynho Road area, the canal served as an important (though awkward) means of transporting the mined ore to its markets.

The one thing we can be certain of is that no Adderbury people ever got directly involved in the canal carrying trade, either as boat owners or captains or crew. This is not only in contrast to the larger canal centres, Banbury and Oxford, but also very different from some other villages – particularly Lower Heyford, Thrupp and Eynsham. We know this because we have the nineteenth-century records kept by George James Dew, Canal Boat Inspector at Lower Heyford, with all the occupants of all the boats inspected and the details of their owners and crews.

Village Attitudes to the Canal

It’s when we come to ask what village people felt about the canal that we begin to understand the gulf between ordinary village life and the life of the canal. Almost from the beginning, and certainly by the time there was competition from the first railways, canal boat people had abandoned life ashore and lived out their lives aboard their vessels. Whole families travelled together, and the all-important task of delivering the load as fast as possible came to dominate family life, with all ages expected to contribute. Not only this, but boat people developed modes of speech, forms of dress, and types of boat decoration all their own, things which cut them off still further from life on land.

Roses and Castles: canal boat decoration

The boat people, however, were not simply perceived to be different: they were actively disapproved of, at least by respectable opinion. Overcrowded boats, it was felt, encouraged immorality, and were no fit environment for growing children. Children were asked to carry out work which was hard and unsuitable, and were denied the educational opportunities which progressive legislation had secured for children onshore. Boat people were known to drink heavily, they failed to attend church and frequently worked on Sundays. Their way of life, it was claimed by their most strident critic, George Smith of Coalville, was not just reprehensible in itself: it also set a bad example to those ashore who came into contact with it.

Of course, North Oxfordshire villagers were far from saintly themselves, and heavy drinking, for example, was as much a problem on shore as it was on the canal. Nonetheless, there were other influences at work which will have reinforced the negative view of canal life being put forward by respectable opinion. First, village families will have known very well that the canal was a dangerous place. The very young and the very old were particularly at risk, nineteenth-century newspaper reports of fatalities make clear, and walking by the canal at night, especially if a public house was involved, could also prove fatal. Another circumstance which may have helped to put the canal in a poor light for the village is the fact that it was quite often the scene of suicides. While we are often told how busy the canal was, the fact remains that there were many remote stretches, even near Adderbury, attractive to those intent on suicide. And it may be that any sense of the dismal nature of the canal would have been made worse for the villagers by the proximity of the village pest house. Known as Carthagena, this building was put up, perhaps at the time of a small pox outbreak in 1750, on land belonging to the town feoffes to the north of the Aynho Road and quite close to the canal. The overseers had to arrange for the isolation, medical attention and burial of the victims. There was a second smallpox epidemic between 1760 and 1770, quite close in time to the coming of the canal.

Competition and Decline

The canal flourished in the first half of the nineteenth century, then, under competition from railways and other canal routes to London, declined until particularly the southern section could be described after the Second World War as a “backwater”. The air of decline was intensified by the fact that Oxford Canal boatmen favoured horse traction long after those on other canals had changed their narrowboats to diesel power.

Perhaps the most telling sign of the gulf between the village and the canal is that there appears to be no mention anywhere at any point in village records of the changing fortunes of the canal. This is in marked contrast to village attitudes to the railway, when it arrived in 1887. Numerous factors contributed to the fact that the railway was quickly adopted as part of village life: it passed through the village, it had regular timetables, offered new destinations, and was staffed by people who were most likely inhabitants of the village itself.

Rebirth

During the 1960s pleasure boating began to grow in popularity and replace the old trading boats across the canal network. The Oxford Canal played its part in the revival of interest in the canals, with Tom Rolt setting off on the journey which would result in his influential book, Narrow Boat (1944), from Tooley’s Boatyard, Banbury, and one of the early activities of the Inland Waterways Association which he helped to found being a boat rally at Banbury over August Bank Holiday in 1955 as part of an ultimately successful campaign to save the canal.

Tom Rolt and Cressy

Adderbury has engaged quite extensively with the new era of canal operation. Moving from north to south, Twyford Narrow Boats, operating from The Old Barn just to the north of Twyford Bridge, is a hire boat operation which also offers boat repairs and servicing, while commercial boat moorings have been offered for hire at Twyford Wharf since 2002. The Canal and River Trust uses the old Nell Bridge Wharf as a maintenance yard, and The Pig Place, north of Nell Bridge Lock, offers stores, provisions and hot meals to passing canal trade.

Phil Mansell

June 2016